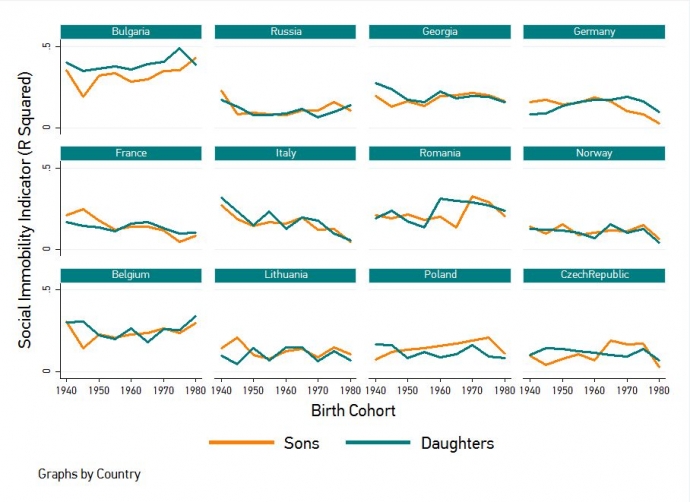

Social mobility is a long standing issue in social research. The GGP offers extensive comparable dataon this topic and a window into the complex dynamics that make up social mobility. In the figure belowwe plot the degree to which a respondent’s father’s education explains his or her own educationaloutcome. The picture it reveals is one of relative stability, in spite of the expansion in higher educationthat most countries have witnessed. This stability is particularly evident in post-socialist countriessuch as Russia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Lithuania where even birth cohorts who undertookthe vast majority of their education after 1989 enjoy relatively high rates of social mobility. However,some countries have shown significant change. In Italy, we can see that an individual’s educationaloutcome has become less dependent on the educational attainment of their father. This is true forboth men and women. Looking forward, new rounds of data collection in the GGP will help update thispicture and understand what the social mobility picture is for millennials and how it is influenced by achanging demographic, social and economic climate.

Social Immobility in 16 Countries by Birth Cohorts

Note: Social mobility is calculated using the R square of an OLS model predicting a respondents’ years ofschooling using their father’s years of schooling. The higher the R square, the more educational attainmentis explained by father’s education. A high score therefore reflects low social mobility and a low scorereflects high social mobility. Data comes from wave 1 of the GGS.

Fill the form below with your contact information to receive our monthly GGP at a glance newsletter.