The Generations and Gender Programme tries to live up to its name. One of the key areas of research in the GGP community is intergenerational relationships. This area of research examines how people from different generations support and rely on each other. This could be a grandparent taking care of a grandchild, a daughter taking care of her elderly mother or parents helping their children pay for university or buy a house of their own. These intergenerational relationships have always been important in society with families pooling resources and sharing responsibilities. However studying these relationships is more important than ever given the changing balance between generations. With people living longer, lower fertility and shifts in the timing of many key life events, it is crucial that social scientists seek to understand the interconnected nature of intergenerational relations. In this Research Note, we examine some of the key dynamics in intergenerational relationships, draw attention to research conducted using GGP data and how this research informs our understanding of the changing relations between generations.

The Generations and Gender Programme tries to live up to its name. One of the key areas of research in the GGP community is intergenerational relationships. This area of research examines how people from different generations support and rely on each other. This could be a grandparent taking care of a grandchild, a daughter taking care of her elderly mother or parents helping their children pay for university or buy a house of their own. These intergenerational relationships have always been important in society with families pooling resources and sharing responsibilities. However studying these relationships is more important than ever given the changing balance between generations. With people living longer, lower fertility and shifts in the timing of many key life events, it is crucial that social scientists seek to understand the interconnected nature of intergenerational relations. In this Research Note, we examine some of the key dynamics in intergenerational relationships, draw attention to research conducted using GGP data and how this research informs our understanding of the changing relations between generations.

The past 25 years have seen considerable change in Eastern European societies following the transistion to post-socialist economies. These social and economic changes have had considerable effects on the demography of these countries and form the basis of many of the challenges that these nations face today. Ageing societies, low fertility and changing families pose questions for policy makers and social researchers regarding the future of this region. In order to answer these questions it is vital that policy makers and social researchers have access to high quality data that enable insightful research and evidence based policy. Here we give examples of how the GGP has helped develop our understanding of some of the developments in this region.

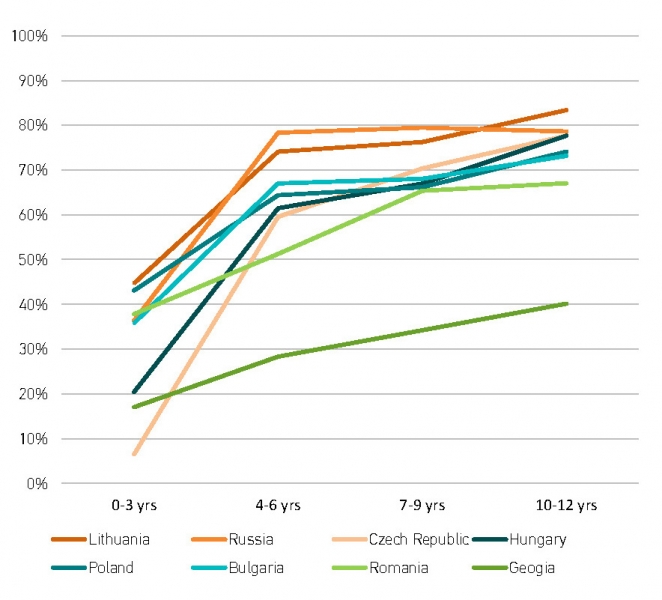

Figure 2 – The employment rate of mothers by age of their youngest child

Since the change of regime twenty years ago, Eastern Europe has seen a large decrease in fertility. This Research Note focuses on whether people are able to realise their plans to have children and uses the results to explore what may have caused the fall in fertility in Eastern Europe over the last two decades. The findings show that individuals in post-communist countries are less successful than western countries in fulfilling childbearing plans and provide evidence of a potential cause.

Figure 1 – The Total Fertility Rate in 4 European Countries since 1990

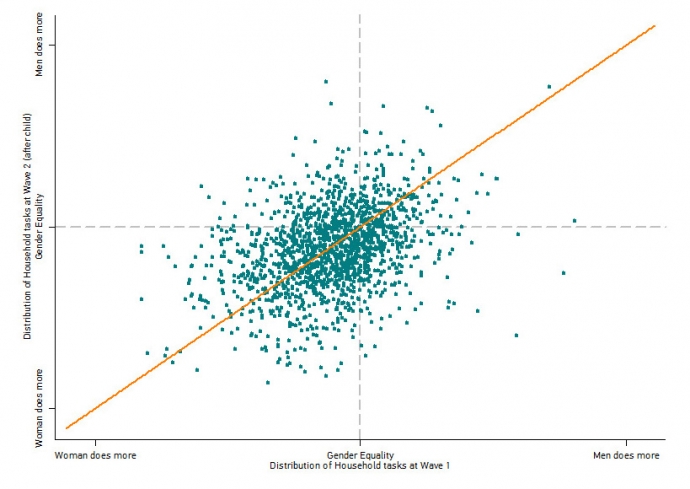

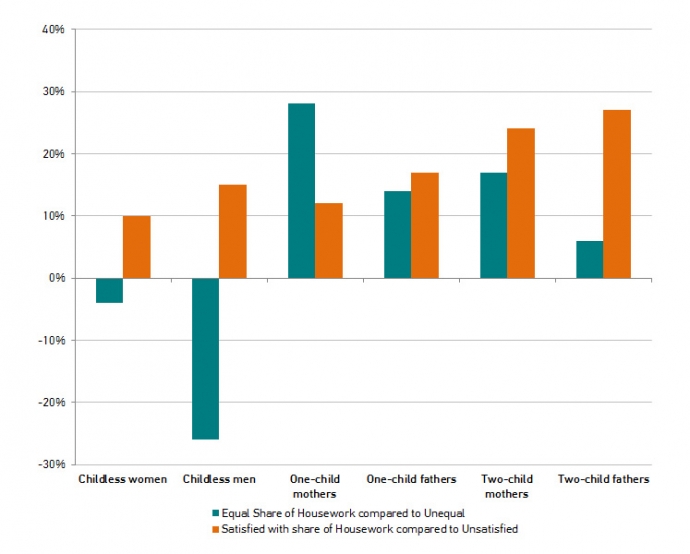

Does gender equality matter for fertility? We studied how three dimensions of gender equality affect the intentions of women and men to have a child in the near future: employment, financial situation, and equity in housework & care. Gender equality in each of these dimensions has a different impact on the childbearing intentions of women and men, but parenthood is still a dividing line between more and less gender equality.

Figure 2 – Likelihood that men & women intend to have a child and its relationship to household work

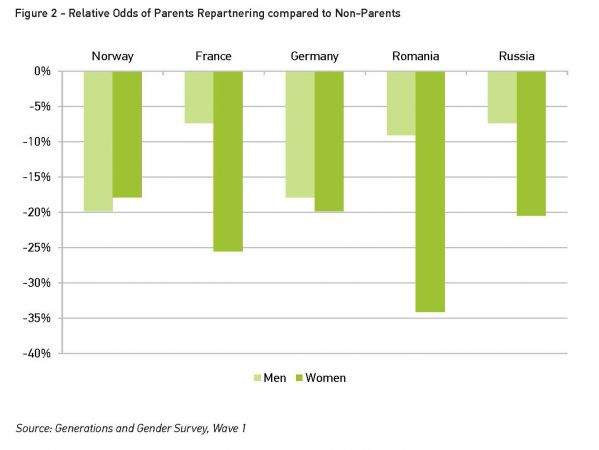

The rise in divorce rates across Europe raises important questions about forming new marital or cohabiting unions. Finding a new partner following divorce can be important because of its potential to counteract some of the negative effects of divorce. For example, divorcee’s generally report lower wellbeing than married people but a new romantic partner has been shown to counteract this. Furthermore, divorce has been found to result in a decline in socioeconomic status, for women in particular, which can be offset by remarriage. The majority of divorcees do re-partner yet the likelihood and the time between divorce and new partnerships can vary greatly between individuals. Our analysis of GGP data shows that women find it harder to find a new partner than men and that this is partly due to women having custody of children from their previous relationship. By looking at five very different countries we show that there are similar patterns across Europe despite differences in custody arrangements.

Fill the form below with your contact information to receive our monthly GGP at a glance newsletter.